[Previous entry: "Phillies Journal - 2004"] [Main Index] [Next entry: "Phillies Journal - 2004"]

09/10/2004 Archived Entry: "Cooperstown Confidential, Sept 9, 2004"

Cooperstown Confidential, Sept 9, 2004

by Bruce Markusen

Rapping With Superjew

If we play a bit of word association and mention the name of Mike Epstein, the nickname “Superjew” comes to mind almost immediately. In today’s politically correct culture, such a nickname for a current-day player probably wouldn’t have much staying power, but times were different in the late 1960s. Recently, over the weekend of August 29 and 30, six Jewish major league alumni (out of a total of 143 in big league history) participated in a two-day celebration of “American Jews in Baseball” at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York. The list of former players included Epstein, a slugging first baseman who played for the Baltimore Orioles, Washington Senators, Oakland A’s, Texas Rangers, and California Angels from 1966 to 1974. During his tenure with the Senators, he played for Ted Williams, an experience that motivated him to become a batting instructor for young athletes in his post-playing days. During his major league career, Epstein established a reputation as a dangerous left-handed slugger on the field and as an emotional, honest, and sometimes confrontational personality in the clubhouse. The following is a transcript of a short interview with Epstein, conducted during the Jewish baseball weekend celebration in Cooperstown:

Markusen: Mike, let me ask you about the first time that you were approached about participating in the weekend. What was your initial reaction?

Epstein: Actually, I didn’t think too much about it. Marty Appel [who coordinated publicity for the event] and I were talking on the telephone and he said, “We’re putting this thing together; would you be interested?” And before I had a chance to say anything, he said, “I’d appreciate it if you would be part of it.” And I said, “That’s all you had to say.” And so I came back and did it not really knowing what I was going to be getting into or what the agenda was. It’s been a magnificent function—for all of us. We’ve all said the same thing. This is really a terrific thing that the people have staged here.

Markusen: It seems like most of the guys have reacted like they’ve gotten more out of it than they even expected going in.

Epstein: Yeah, I think so. For me, it’s fun to be amongst Jewish people who, when you stop to think about it, Jewish people are some of the greatest supporters of the game of baseball. They’re just rabid fans. It’s fun to be around people with that kind of passion.

Markusen: I guess it was one of your minor league coaches, Rocky Bridges, who came up with the “Superjew” nickname. What did you think of that when you first heard it? How’d you take it?

Epstein: Well, it was a compliment, because I had just hit a ball over 500 feet, and I remember Rocky saying as we passed one another, him to coach third base and me to play first base, he said, “Nobody’s ever going to catch that one, Superjew.” And so the next day I came in the clubhouse and the clubhouse boy had written “Superjew” on all my undergarments. I just didn’t really think much about it, certainly not in terms of being offensive but really as a form of being a compliment. It wasn’t something that I ever fostered or tried to continue. To me, there was no continuity in the nickname. But there really was, because my nickname became “Supe,” which was short for Superjew on all the teams that I played for. And then I look in the official encyclopedia of baseball and under my name it has in parentheses, “Superjew.” So I guess I’m not able to get away from it.

Markusen: Mike, in 1972, when you were a part of the Oakland A’s’ first World Championship, you and Ken Holtzman made what I think—and I think most people would agree—were very nice gestures when you wore black armbands on your uniforms in honor of the slain Israelis killed at the Olympic Games. Tell us how that started, whose idea it was, and what it meant at the time?

Epstein: Well, I’m not really sure whose idea it was. But I remember that Kenny and I always spent a lot of time together; we were very close friends. We were in shock. We were in Chicago to play the White Sox, when we heard about the Munich tragedy; we just looked at one another. I’m sure there were a few epithets that came out of our mouths at that time. I don’t remember us saying anything for the next three or four hours; we just walked the streets of Chicago. I mean we were just dazed by what had happened. Not really sure how we came up with the idea, but I think as we look back in retrospect it was something that we felt that we had to do. But it wasn’t anything that we made a conscious decision to do.

Markusen: Final question for Mike Epstein. When you look back at those days with the A’s, was that the highlight of your career—considering the World Championship, all the things that were going on between Charlie Finley and various players, between the players themselves, the whole “Mustache Gang” thing—was that the favorite episode of your career, if you will?

Epstein: Well, playing in a World Series is always a highlight. There’s a lot of great players who never get that opportunity, so I’m very fortunate to have had that opportunity. Actually, there’s quite a few highlights. Another one is having the opportunity to play for Ted Williams and to mentor under him as a hitting instructor for 10 years. That’s an opportunity also that’s been afforded to very, very few. And quite honestly, just being able to step out on a baseball field, and representing Jewish people when you cross the white lines is also a huge highlight for me. I’ve always taken that very seriously; I do to this day. I’m very proud of my heritage and ancestry.

There are a lot of highlights. And the A’s’ win [in 1972] was, of course, too. Believe it or not, it was a very close-knit team. We had a lot of individual personalities, we had a lot of strong people, and we just told it the way it was. But then when we crossed those white lines, boy… If Finley had just kept his act together, that team could have won 10 World Series in a row, because everybody was really young. But, you know, that’s just the way the game goes.

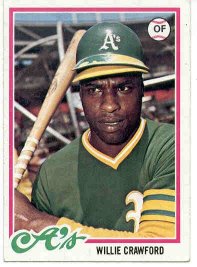

Card Corner (with thanks to Chris Dial for supplying this week’s card image)

Earlier this year, I started work on a Card Corner feature profiling journeyman outfielder Willie Crawford. Motivated by Crawford’s unusual decision to wear No. 99 for the Oakland A’s in 1977, I wanted to learn more about this once-promising star who never quite fulfilled the predictions of greatness made for him. I thought about writing Crawford a letter to ask him about the choice of uniform numbers and collect his thoughts about irascible owner Charlie Finley, but never got around to doing it. Sadly, there will be no chance to write that letter now, what with the news of Crawford’s passing from kidney disease in late-August. Though it remains unfinished because of my procrastination in writing to Crawford, this week’s Card Corner is offered in memory of the former Los Angeles Dodgers phenom:

For one major league team owner, Willie Crawford epitomized the notion of “the one who got away.” And by the time that the owner in question finally reeled him in, he found himself with a player who fell well short of the high expectations that had once encompassed his future.

In 1964, the 17-year-old Willie Crawford drew the interest of almost every one of the 20 major league teams in existence. With his combination of power, speed, and throwing arm, clubs like the Los Angeles Dodgers, New York Yankees, and Kansas City A’s envisioned him as a centerpiece in their outfield futures. Dodgers executive Al Campanis filed a scouting report that said Crawford “hits with the power of Roberto Clemente and Tommy Davis at a similar age.” Kansas City A’s owner Charlie Finley lifted the level of praise even further, calling Crawford “a Willie Mays with the speed of Willie Davis.”

Finley liked Crawford so much that he gave the youngster a large, framed, signed portrait of himself, which eventually hung in the Crawford living room. Even more pertinently, Finley offered Crawford a bonus of $200,000 to play center field for his A’s—more than any previous bonus given to an African-American player. Crawford seemed genuinely intrigued by the advances of Finley, referring to him as “one of the nicest millionaires I know.”

Yet, Crawford turned down the millionaire’s offer, instead signing a $100,000 bonus contract with the Dodgers. As a native and resident of the Watts section of Los Angeles, Crawford simply didn’t feel comfortable about moving away from the California coast. He also found himself swayed by Dodgers scout (and future Hall of Fame manager) Tom Lasorda, who had taken the time to attend the funeral of Crawford’s grandfather.

The Dodgers, like the A’s and Yankees, expected Crawford to become a superstar. It didn’t happen. Crawford’s outfield play, crude and untrained, left much to be desired. Crawford also struggled to hit left-handed pitching, so much so that the Dodgers cast him in the role of a platoon player. Frustrated by a lack of consistent playing time, Crawford struggled with his weight—and with alcohol. Allowing his problems to fester, Crawford didn’t tackle the latter obstacle until 1981, when he received treatment at The Meadows, an acclaimed center for alcoholic rehabilitation.

By the mid-1970s, Crawford had firmly established his status as a major league journeyman. He bounced from the Dodgers to the St. Louis Cardinals to the Houston Astros. Then, in the middle of the 1977 season, Crawford found himself traded again. This time he landed with the Oakland A’s, who had since moved from Kansas City but were still owned by Charlie Finley. The trade eventually resulted in this 1978 Topps card, his only card as a member of the A’s—and his final trading card, as well.

The move to the A’s left both the owner and the player dissatisfied. The most memorable moment of Crawford’s tenure in Oakland was probably his decision to wear No. 99 on the back of his jersey. Other than that, not much of note happened. Nearing the end of his career, Crawford hit a measly .184 in a half-season, looking little like the talent that Finley had once compared to Willie Mays. Crawford didn’t like playing for the A’s, either. “It was depressing,” Crawford told The Sporting News. “They went with the kids. I was just a spectator up there.” As for his relationship with Finley, the man he had once called the “friendliest millionaire” he ever met, Crawford was able to offer little insight. “I didn’t have any communication with the man,” Crawford said bluntly—and perhaps with a bit of sadness. Perhaps Finley would have talked to him more if only Crawford had started his career with Kansas City in his prime, rather than end it in Oakland as an obscurity.

Celebrating The Splinter

This weekend (September 11 and 12), the Hall of Fame will kick off the first of two major events scheduled in honor of Ted Williams. (The second event is scheduled for the spring of 2005.) I’ll be one of the scheduled speakers, along with Williams’ former Red Sox teammate Bill Monbouquette and former Sports Illustrated columnist Leigh Montville. With thanks to SABR member Bill Nowlin for organizing and overseeing the event, here’s the complete schedule of speakers this weekend in Cooperstown:

Saturday, September 11

10:00 am: Bruce Markusen, author of Ted Williams: A Biography, discusses Ted Williams’ tenure as manager of the Washington Senators and Texas Rangers.

11:30 am: Dave McCarthy, executive director of the Ted Williams Museum, talks about Ted’s involvement with the museum and the Hitters Hall of Fame.

1:30 pm: Author Leigh Montville discusses his recently published book, Ted Williams: A Biography of an American Hero.

3:00 pm: Steve Ferroli talks about his involvement with the Ted Williams Baseball League.

Sunday, September 12

10:00 am: Alan Pierce discusses Williams and popular culture, including ephemera and memorabilia.

11:00 am: Historian and author John Holway remembers Ted as a well-liked ballplayer.

1:00 pm: Bill Nowlin, a Williams biographer and expert, discusses Ted Williams’ Mexican heritage.

2:00 pm: Bill Monbouquette, teammate of Ted Williams in Boston and now a minor league pitching coach for the Oneonta Tigers, offers some of his favorite stories about the “Splendid Splinter.”

Pastime Passings

Bob Boyd (Died on September 7 in Wichita, Kansas; age 84; cancer): Nicknamed “The Rope” for his ability to hit line drives consistently, Boyd enjoyed a nine-year career in the major leagues. In 1957, as a member of the Baltimore Orioles, he finished fourth in the American League batting race with a .318 batting average. He also played for the Chicago White Sox, Kansas City A’s, and Milwaukee Braves. Although he was a tough left-handed batter and a capable fielder, Boyd lacked the power that most teams preferred in a first baseman; as a result, he spent much of the latter stages of his career as a pinch-hitter. Boyd finished his career with only 19 home runs, but batted .293 in 693 major league games.

Willie Crawford (Died on August 27 in Los Angeles, California; age 57; kidney disease): A veteran of two World Series, Crawford was once the most highly recruited high school player in the country. In 1964, the Los Angeles Dodgers signed him to a contract that included a bonus of $100,000, mandating that Crawford be kept on the 25-man roster the entire season. As a result, Crawford made his major league debut that season at the age of 17. He remained with the Dodgers for 12 seasons, but never lived up to the billing of many major league scouts, who raved over his speed, power, and outfield throwing arm. Used primarily in a platoon role, Crawford made his first World Series appearance in 1965, delivering a pinch-hit single in Game One against the Minnesota Twins. Crawford enjoyed his best season in 1973, when he batted .295 with 14 home runs and 66 RBIs. The following year, he made his second appearance in the World Series with the Dodgers and hit a home run, but couldn’t prevent LA from losing the so-called “Freeway Series” in five games. In 1977, the Dodgers finally traded Crawford, who finished up his career by playing short stints with the St. Louis Cardinals, Houston Astros, and Oakland A’s.

Hal Epps (Died on August 26 in Houston, Texas; age 90): A longtime minor league star and a member of the 1947 Texas League champion Houston Buffs, Epps appeared in 125 major league games over a staggered four-year career. Making his debut for the St. Louis Cardinals in 1938, Epps hit a home run in his first at-bat—marking the only home run of his big league career. The left-handed hitting outfielder finished his rookie season with a .300 batting average in 50 at-bats, but didn’t return to the major leagues until 1940 and never again achieved similar success. In 1943 and ’44, he wrapped up his big league career by playing short stints with the St. Louis Browns and Philadelphia Athletics. Playing in his final season with the Athletics, Epps collected nine triples, which placed him in the top five in the American League. Rather than retire, Epps decided to continue his playing career in the minor leagues.

Madeline “Maddy” English (Died on August 21 in Everett, Massachusetts; age 79; lung cancer): A veteran of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League from 1943 to 1950, English starred on two league championship teams. After graduating from high school in 1943, English signed with the Racine Belles, whom she helped win league titles in 1943 and 1946. She forged a reputation as one of the league’s better third basemen and later became a popular physical education teacher in Everett, eventually earning induction into the Women in Sports Hall of Fame, the New England Sports Museum, and the Boston University Hall of Fame. A school in Everett is also named in her honor. English remained a fan favorite in her later years, often attending reunions of the AAGPBL and celebrations of Women in Baseball at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

COMMENTARY: I was fortunate to get to know Maddy English through her frequent visits to Cooperstown as part of Mother’s Day events at the Hall of Fame. She reminded me of a female version of Phil Rizzuto: very self-deprecating with a good sense of humor. She was modest about her playing abilities, which were good enough to earn her three All-Star selections, but still took rightful pride in a Massachusetts’ school’s decision to rename itself in her honor. Yes, Maddy was one of the good ones. Those AAGPBL reunions won’t be quite the same without her.

Cooperstown Confidential author Bruce Markusen is the author of four books on baseball, including the newly-published Ted Williams: A Biography (Greenwood Press), now available at www.greenwood.com and www.amazon.com. And for those interested in the realm of horror and vampires, Markusen’s other new book, Haunted House of the Vampire, will be available in October. Markusen is also co-host of “The Heart of the Order: Old School Baseball Talk,” which airs each Thursday at 12 noon Eastern time on MLB.com Radio. For more information, send an e-mail to bmark@telenet.net.