[Previous entry: "Phillies Journal - 2004"] [Main Index] [Next entry: "Phillies Journal - 2004"]

07/03/2004 Archived Entry: "Cooperstown Confidential - July 1, 2004"

Cooperstown Confidential - July 1, 2004 by Bruce Markusen

Harper And The Hall

One of the grand misconceptions about the Hall of Fame is that it’s all about the Hall of Famers. In actuality, the Hall’s Plaque Gallery, where small monuments to each of the 256 enshrined members are permanently housed, comprises only a small percentage of the Museum’s physical space. There are about 16,000 other players who performed in the major leagues, with all of them receiving representation in the vast clippings files of the Hall of Fame Library’s archive. (Each player has his own file, though some files for obscure and old-time ballplayers are currently empty.) And from time to time, some of those players visit Cooperstown, becoming guests of the Museum in what has become known as the Hall of Fame’s Legends Series.

Last week, the latest incarnation of the Legends Series featured former major league star Tommy Harper, who took part in a moderated Q-and-A in the Bullpen Theater and then fielded questions from the audience. By no means a Hall of Fame caliber player, Harper nonetheless achieved stardom at the peak of his career, combining speed, power, and versatility in a way that few players of his era were able to match. Although Harper is one of the players whose Topps cards I’ve aggressively collected over the years and remains a favorite of mine today, I have to admit I was a little leery of hearing him speak. I had heard that he was bitter about racist treatment that he had endured during his career, in particular the time that he served as a coach with the Red Sox and was not permitted to visit a restricted country club during spring training. (Thankfully, the Red Sox have since changed that policy.) In addition, I remembered our own efforts to interview Harper in spring training a few years back; we had wanted to ask him a few questions about Carlton Fisk, who was about to be inducted into the Hall, but Harper turned us down flat, leading me to believe he might be less than ideal in the setting of a public speaking venue.

Much to my pleasure, my preconceived notions turned out to be nothing more than unnecessary worries. Though he appeared a bit grizzled, with lines of age pocking his face and his hair heavily receded, Harper was well-spoken and cordial, and sprinkled his responses with easy bursts of humor. In truth, he couldn’t have handled the questions from the audience with more respect and charm. He also proved quite insightful, revealing some previously unheard details of a career that I thought I knew very well. For example, Harper informed us that he played high school baseball with Hall of Famer Willie Stargell (as an avid Stargell fan, I was surprised to hear about that), but that their teams never won any championships. Growing up in the Bay Area in the 1950s, Harper followed the Pacific Coast League’s Oakland Oaks, who served as predecessors to the major league A’s (who didn’t arrive in Oakland until 1968).

With the hometown San Francisco Giants showing little interest in his services, Harper signed with a Midwestern team—the Cincinnati Reds. Playing as an infielder, he worked his way quickly through Cincinnati’s farm system. In 1962, an injury to veteran third baseman Gene Freese opened up a spot in the lineup; when manager Fred Hutchinson asked Harper if he could play the hot corner, he said yes, of course, not mentioning the 34 errors that he had made at Triple-A San Diego.

In 1963, the Reds moved Harper to second base, but that left him in competition with a youngster named Pete Rose. Although Harper was the better athlete, Rose’s superiority as a hitter helped him win the job and forced Harper into another position switch. This time, the Reds moved Harper to the outfield. With Vada Pinson in center field and Hall of Famer Frank Robinson in right field, Harper was funneled toward left field—where he won the job amidst some stiff competition. Essentially playing his first full season as a major leaguer, Harper received guidance from three primary sources: Robinson, shortstop Eddie Kasko (who would later become his manager), and future Reds skipper Dave Bristol. A player from an opposing team also gave him some needed guidance. Facing the insecurities that most young players encounter in wondering whether they belong in the big leagues, San Francisco’s Felipe Alou reminded him that “there are other jobs.” In other words, failure in the major leagues wouldn’t—or shouldn’t—prevent Harper from achieving success in another area.

Fortunately, Harper didn’t need to pursue another line of work anytime in the near future. Helping to form one of the game’s most athletic outfields (along with Pinson and Robinson), he remained with the Reds through the 1967 season. The Reds then dealt him to the Indians, where he struggled through a lost season before being left available in the expansion draft. The new-look and talent-starved Seattle Pilots selected Harper, in what turned out to be one of the biggest breaks of his career. Although the Pilots challenged Harper by returning him to second base on a part-time basis, making him the Alfonso Soriano of his day (his defensive skills were decidedly lacking on the middle infield), they also made him the centerpiece of their offense—both as a leadoff man and as a premier basestealer. Unlike his days in Cincinnati, when he could steal only when given the appropriate sign, Harper was given free reign on the basepaths. “You’re on your own,” Pilots manager Joe Schultz told Harper, realizing that Seattle needed to run the bases aggressively to make up for a lack of power—and overall hitting—throughout their lineup. Harper took full advantage of Schultz’ permission slip, swiping a career-high 73 bases to lead the American League. Harper’s dominance on the basepaths only confirmed his own high self-esteem in his basestealing ability. “[In stealing bases] I felt I was just as good as Lou Brock,” Harper says.

During his session in the museum, Harper was asked about his relationship with Jim Bouton, the author of Ball Four, which followed the exploits of the Pilots for most of the summer. “We didn’t know he was writing the book,” says Harper. “I’ve never read the book. But he was generous to me.” Unlike Joe Schultz and pitching coach Sal Maglie, Harper managed to escape the wrath of Bouton’s pen. “Joe Schultz was upset. Bouton and Joe Schultz were never friends after that.” Harper, however, seems to carry no resentment toward Bouton for having written a behind-the-scenes book about day-to-day life with the Pilots.

In 1970, Harper anticipated a return to Sicks Stadium, the Pilots’ decrepit minor league ballpark. With his car waiting in Seattle, Harper reported to the Pilots’ spring training site in Tempe, Arizona. Only days before the start of the regular season—and without warning to him—Harper was left stunned when he heard that the franchise had not only been sold but would also move to Milwaukee on a moment’s notice. Saddled with an unwanted expense, Harper had to pay a college student to drive the car from Washington to Wisconsin.

In adjusting to new surroundings, including much colder weather conditions, and a new playing role (the Brewers made him a fulltime third baseman), Harper endured a slow start to the 1970 season. The inauspicious beginning in Milwaukee didn’t prevent Harper from having his best year; he surpassed 30 stolen bases and 30 home runs, becoming the first infielder to achieve the 30/30 plateau. Harper’s command of both the basepaths and the long ball earned him the nickname “Tailwind Tommy.” Harper didn’t particularly like the nickname, but accepted it without complaint.

Two years later, the trade winds forced Harper to move his power-and-speed show to Fenway Park, as part of the George Scott/Jim Lonborg 10-man blockbuster. In 1972, he came within a half game of his first trip to the postseason; unfortunately, the handful of games lost to the player strike left the Red Sox playing one less game than the Tigers—the difference in an unfairly decided divisional race. Still, Harper enjoyed playing in Boston, especially with former Reds teammate Eddie Kasko now serving as manager. He also became good friends with staff ace Luis Tiant and came to appreciate the strangeness of Bill Lee, with whom he frequently rode to the ballpark. Harper’s happiness in Beantown was reflected by his performance on the field. Playing his second season with the Red Sox in 1973, Harper swiped a league-leading 54 bases to set a franchise record for most stolen bases in a season. He also hit 17 home runs that summer with a respectable .281 batting average.

By the mid-1970s, Harper found his way to Charlie Finley’s kingdom in Oakland. Unlike many of Finley’s former players, Harper speaks charitably about the A’s’ onetime chieftain. Although Finley had a reputation for cheapness (for example, he charged players whenever they broke bats in fits of anger), he also displayed a more generous side. In 1975, Finley extended an offer to Harper and his teammates. “He said that you could have $500 if you grew a beard,” Harper recalls. “So I grew a beard.” Harper also earned another $500 for wearing a cowboy hat on one of the A’s’ road trips. Ah yes, that was pure Finley.

Aside from strange incentives and bonuses, the 1975 season also brought Harper to the postseason for the first time in his long career. As champions of the AL West, Harper and the A’s fell to his former team, the Red Sox, in a surprising three-game playoff sweep. Having lost to his former teammates, Harper playfully needled Red Sox star Carl Yastrzemski. “Yaz, you never hit Vida Blue when we were teammates,” says Harper, recalling his good-natured conversation with the Hall of Famer.

After wrapping up his career with a short stint in Baltimore, Harper remained passionate about baseball and turned to coaching. He worked for the Expos for 10 seasons, suffering more postseason frustration in 1994, when Montreal’s sizeable lead in the National League was wiped out by the latest disagreement between the players and owners. As with the playoff series loss in 1975, Harper continues to maintain his sense of humor about never having reached the World Series as a player or coach. He’d like to get there in some capacity, but it won’t kill him if he doesn’t.

In spite of the problems he once endured with Red Sox management, which used to provide admission to an all-white country club that excluded black players and coaching personnel, Harper has long since returned to the Boston organization. He serves as a roving minor league instructor, traveling throughout the farm system while working with young players on hitting and baserunning skills. And when asked to name his favorite team as a player, he offers no hesitation in saying simply, “the Red Sox.”

Tales of Trades

I’ll leave the heavy lifting to the Sabermetric analysts in assessing last week’s two major trades, but a couple of thoughts struck me as pertinent in regards to the blockbuster deals. First, Astros manager Jimy Williams deserves some credit for keeping newcomer Carlos Beltran in center field and moving stand-byes Craig Biggio to left field and Lance Berkman to right field. Too often managers are afraid to change the positions of their established team stars—especially in the middle of a season—even when it makes the most sense. Of the three Astros’ starting outfielders, Beltran is clearly the best center fielder, and that’s where he should play, even if it means exposing him to Tal’s Hill at Minute Maid Park. The aging Biggio, who was just an adequate center fielder, should be more comfortable in left. As for Berkman, he has enough of an arm to play right, which makes him a better fit for that position. Now all of these mid-season adjustments may involve some growing pains, but the transition should be complete by July 31, when the Astros will know whether they are real contenders or also-rans. If the Astros fall out of the race, they can still trade Beltran at that time, knowing that some contender will be looking for an extra bat… As for the Mariners, their front office deserves credit for trading Freddy Garcia at just the right time and extracting more than market value from a White Sox team that has become desperate for starting pitching. Any time that a general manager can acquire two young starting position players (catcher Miguel Olivo and outfielder Jeremy Reed) for a pitcher on the cusp of free agency, he should be applauded for making such a deal. (And if minor league shortstop Michael Morse becomes any kind of a player, this becomes an absolute steal for Seattle.) In one fell swoop, the Mariners upgraded two spots in their lineup in exchange for a pitcher they were unlikely to re-sign. Bill Bavasi deserves kudos for starting the rebuilding process with a bang in the Great Northwest.

The Nickname Game

While reading through Chris Devine’s underrated book, Thurman Munson: A Baseball Biography, I came across a nickname that had previously eluded my mental clutches. Little did I know that former Yankee third baseman Rich McKinney was known as “Orbit,” apparently for his aloof, detached-from-reality manner. Known for his wild, curly hair, McKinney remains part of the Yankees’ legacy of infamy; after the 1971 season, the Yankees acquired him from the White Sox for Stan Bahnsen in a deal that was panned by Pinstriped fans almost from the start. Expected by Yankee management to fill the third base void that had been created five years earlier by the trade of Clete Boyer, McKinney was overmatched both at the plate and in the field. He’s best remembered for committing four errors in one game, and when that’s your legacy in New York, you won’t be recalled quite as fondly as Graig Nettles or Mike Pagliarulo… It’s too bad that McKinney isn’t an active player today. If he were, his “Orbit” moniker would make him a perfect spokesman for the gum company of the same name, the one that seems to specialize in peculiar commercials. I do like the gum, however.

Card Corner

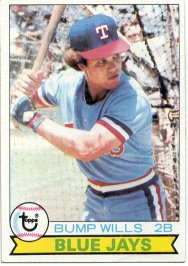

Simply put, this is one of the most famous error cards in the history of baseball memorabilia. In 1979, the Topps Company produced a Bump Wills card featuring him as a member of the Toronto Blue Jays, even though he was clearly still playing for the Texas Rangers. So what happened here? Two years ago, former Topps president and baseball card icon Sy Berger visited the Hall of Fame for a 50th anniversary celebration of Topps, giving me the opportunity to ask him directly about the reasons behind the Wills mistake. According to Sy, he had received a call from a friend after the 1978 season, telling him that Wills was about to be traded from the Rangers to the Blue Jays as part of a blockbuster deal. Although the trade had yet to be announced, the friend assured Berger that it was a “done deal.” Convinced that he had a scoop and figuring that he could release an accurate and updated card ahead of the curve, Berger instructed his production people to attach the name “Blue Jays” to the bottom of the Wills card. After producing the card during the winter of 1978, Topps issued it to the public in March, which was typically the time that Topps released its cards during the late seventies.

Unfortunately, like many trade rumors, the Bump Wills “trade” turned out to be nothing more than rumor. The Rangers never did deal their veteran second baseman, who had previously been best known for being the son of former basestealing champion Maury Wills, instead keeping him in Texas for the 1979 season.

With the trade falling through, Topps was left mildly embarrassed. Once Opening Day rolled around and Berger realized that no trade was going to take place, Topps decided to correct the error and release a revised and corrected card, this time showing the name “Rangers” at the bottom of the card. As a result, there are two 1979 Bump Wills cards in circulation. The corrected “Rangers” version is considered the more valuable, since fewer of those cards were produced, making it scarcer than the “Blue Jays” version. The only thing scarcer might be Berger’s relationship with his friend, who had clearly given him some misguided information and had ceased becoming a source of knowledge for the Topps Company.

Pastime Passings

George Hausmann (Died on June 16 in Boerne, Texas; age 88; cancer): After debuting for the San Francisco Giants in 1944 and ’45, Hausmann jumped the major leagues to play in the Mexican League. Commissioner A.B. “Happy” Chandler suspended the second baseman, but eventually lifted the ban. Hausmann later returned to the Giants, playing for them briefly in 1949. In 301 career games, he batted .268 with three home runs and 10 stolen bases. After his playing days, Hausmann managed several minor league teams before completely leaving the game.

Wilmer Fields (Died on June 4; age 81; extended illness): A well-known player in the Negro Leagues, Fields starred as both a pitcher and third baseman for the Homestead Grays and later became the president of the Negro League Baseball Players Association. Playing for the Grays from 1939 to 1950, Fields enjoyed one of his finest seasons in 1942, winning 15 games according to available records. Also a standout player in the Caribbean, Fields won the 1950-51 batting championship in the Venezuelan Winter League.

Floyd Giebell (Died on April 28 in Wilkesboro, North Carolina; age 94): Although he pitched in only 28 games, Giebell helped the Detroit Tigers secure the American League pennant in 1940.

Needing a win to clinch the league title, the Tigers called on the lean right-hander to start the game on September 27 against future Hall of Famer Bob Feller of the Cleveland Indians. Hurling a six-hit shutout, Giebell bested Feller and the Indians to send the Tigers to the World Series. The Tigers rewarded Giebell by giving him a silver tray engraved with the signatures of the team’s players. The young right-hander never again achieved similar glory. He pitched briefly for the Tigers in 1941, but was sent back to the minor leagues in mid-season. After pitching for Buffalo in 1941 and ’42, he then served in the U.S. military for three years during World War II. Never returning to the major leagues, Giebell finished his career with a 3-1 record and a 3.99 ERA in 28 games encompassing over 67 innings.

Cooperstown Confidential author Bruce Markusen is co-host of the Hall of Fame Hour, which airs each Thursday at 12 noon Eastern time on MLB.com Radio. He is also the author of three books on baseball, including A Baseball Dynasty: Charlie Finley’s Swingin’ A’s, Roberto Clemente: The Great One, and The Orlando Cepeda Story. A fourth book, Ted Williams: A Biography (Greenwood Press), is scheduled for release this fall. Markusen is also available for lectures and presentations on baseball and baseball history. For more information on lecture availability, send an e-mail to bmark@telenet.net.